Translations:

Other Pages:

CEC Training Modules

Akan Studies Site Map

Sociology for beginners

Contact

Kompan Adepa

Go to the People

Ghana Web

Ancestors I

Death and Beyond

by Phil Bartle, PhD

In contrast with the gods, who are concerned with health, fertility and well being, the ancestors, as they were when alive as chiefs and elders, are concerned with power, settling disputes, protocol and political organization.

The word "saman" means ghost. The respectful way to call the ancestors when pouring a libation is "Nananom Nsamanfo" (nana = grandparent, nom = plural, fo = people). Most libations (prayers) include calling the Supreme Being, Mother Earth, the gods and the ancestors. Gods may be named or not, and ancestors, or their matrilineage or matriclan names, may be identified, or not. The shortest libation I have heard, when drinking palm wine, swilling the dregs and making them go "plop" when they hit the earth, is "Aso."

Death and Ancestor Homage

Being dead is not sufficient a requisite for being an ancestor. Many events and conditions of your life affect your status after death.

The higher your status during your life, the bigger an event your funeral will be. The bigger your funeral, generally, the higher your status after death. Size of funeral depends upon your status during life.

Inequality is a fact of life in Akan society. It may not be based directly on relations to production, because land, the key factor of agrarian production, is owned by corporate matrilineages. For an individual, status in society depends to a large extent upon the number of offspring he or she has. Within any lineage, some members may be sacred, as being possessed by their own ancestors, and called elders. Lineages, in turn, vary in status, power and wealth. The funeral of a chief is grand, extensive and elaborate. The funeral of an elder of a lesser lineage is also extensive, but not so much.

Similarly, a person who is an כkomfo (priest or priestess) of an important tutelary deity, will have a large and elaborate funeral.

A person may be very popular during life, generous, altruistic, dependable, a contributor to the community or to society at large. His or her funeral may be big, even when his or her status might not be so high. Similarly, persons who have non traditional (modern) professions or occupations will be highly respected ─doctor, professor, member of parliament─, and their funerals will be larger and more elaborate.

At the bottom of the hierarchy is an infant who dies a few days after birth (pot child). They are considered to be mischievous and vandalous spirits, and there is no funeral for them. Their parents are not permitted to cry or grieve. Instead the parents are encouraged to be happy that they are rid of that bad spirit, given a meal and told to "di" (a word that means both to eat and to have sex) ─ get on with life, grow and produce more children.

Funerals

Large funerals serve more than to mourn the deceased and to help them on the way to the land of the dead. Funerals are also times when large numbers of people return to their home town. It is therefore a time for your people to meet other young people, to strike up liaisons, and eventually to find marriage mates.

|

|

|

In Obo During a Funeral

Funerals serve important social functions beyond mourning and as rites of passage. Large numbers of dispersed community members return to the home town, and this becomes a good time to meet potential marriage mates and new playtime friends. Relations between long time friends –– individuals and lineages –– are reinforced. Minor disputes are solved. Business deals are conceived and hatched.

Funeral Colours

In my article, Three Souls, I explain about the cosmography of the three core colours, red, black and white. The colour white is not worn by live participants at a funeral, because it signifies joy, and is worn to celebrate a successful rite of passage. The corpse is usually dressed in white, or in bright colours which belong to the white category (eg kente), to signify a successful change in status. The body may also be covered in white powder, much like an כkomfo in preparation for possession by a god.

|

Wearing a Funeral Cloth

When you see most of the people in town wearing red or black, or sombre colours (including brown, rust, dark orange and shades of red), then you can be sure a large and important funeral is taking place.

|

Carrying the Coffin

If, while they are carrying the coffin, the pallbearers feel that there is a pull towards some direction, they follow the pull. If the coffin then moves towards a specific person, that person is suspected of having killed the deceased, usually through witchcraft.

|

|

Young Man Demonstrating How to Wear Cloth (Adinkra)

Although an adinkra cloth is stamped with traditional Akan symbols, in this funeral cloth they cannot be easily distinguished because they and the cloth are both black.

Funeral Dolls

|

|

Funerary Terracottas

These terracottas (clay images of humans) are made by women as are all items made from clay. They are used as headstones or sentimental images as photos may be used in European societies. They are kept in ancestral stool rooms of lineages important enough to have them, or hidden away in the houses of lesser lineages. Two elements of Akan notions of beauty are exaggerated, rings around the neck, and high foreheads. In that way they resemble the wooden dolls used for fertility (made by men because they are carved).

|

Old Photo

More frequently, as time passes, old photos of the deceased are used instead of the clay objects.

Participation of the Ancestors

|

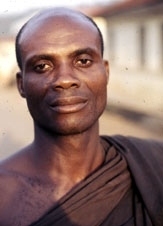

He calls the ancestors as well as the gods

The ancestors are not only respected, they are invited to participate in all public functions (as are also the gods). A prayer is in the form of an offering of alcohol, calling the ancestors to attend.

Perhaps this element of traditional Akan religion should be called Ancestor Homage rather than Ancestor Worship. It is not as if the ancestors are not spirits; it is that they are not seen as holy like saints. They are respected, and they have power, just as they did as elders and chiefs when they were alive. And they are considered present and participating members of the community and lineage. The opening of any new meeting or new case by pouring a libation of alcohol is intended to call them to pay attention and participate. Both gods and ancestors can be quite capricious; they are very human.

A libation usually begins with the mention of the Supreme Being, Onyankepon Tweduampong (The Supreme Shining One who is like a tree or plank on whom we can always be supported). "Drink Alcohol." Then Mother Nature (Earth Woman born on Thursday). "Drink Alcohol."

Then the Gods and Ancestors are mentioned. If ancestors are called, then perhaps a few by name, and their matrilineages, or perhaps the statement "If I call one, I call all." Similarly, if the gods are called, perhaps a few by name, then perhaps a list of rivers and mountains. Again, to shorten the list, the person pouring the libation may say "If I call one, I call all." The length of the libation is variable, and can be drawn out by listing more names, lineages or gods. In more formal and more serious situations, the libation tends to be more longer and detailed.

Then the person pouring the libation may say a few standard statements, such as, "We hold no evil in calling you," or "You are the staff on which we can lean on and you will never fail." After that the person pouring the libation will state the reason for the case or event, to recognise a new person's identity, the settling of a dispute, the blessing of a new institution, ... whatever.

The ending of the libation may then be a few similar standard statements.

When a linguist or someone important pours the libation, it is the duty of the rest present to answer after each phrase, "Hwe" or Wjeh" (listen; look; pay attention) in a call and answer pattern. Done well it is very harmonious. Often only other elders or even only other linguists will chant the replies.

The prayer assures the attendance, attention and participation of the gods and ancestors.

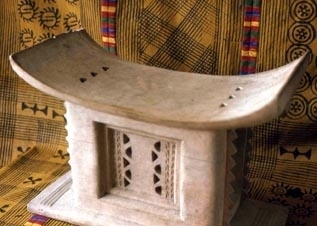

Ancestral Stools

More important politically than funerary terracottas are ancestral stools. By a process of contagious magic, a bath stool used by an elder or chief, when he or she is living, is considered to have stored up much of the "power" of the living person. It is therefore kept and revered after death.

|

|

When an elder or chief dies, her or his bath stool is marked with boto on its bottom

The cloth behind this stool is adinkra, stamped with traditional Akan symbols. Adinkra stamps are made by carving soft fresh calabash fruit and allowing them to harden.

If the fortune of the lineage rises, the ancestral stool also may undergo increases in status.

A stool may be promoted to an ancestral stool by being blackened. Medicinal powder, called boto, is mixed with egg or egg albumen into a paste which is put onto the stool as a lacquer. The lacquer hardens and the stool is black. More about boto in Health and Fertility.

Ancestral stools are not usually allowed to be seen in public because jealous persons and spirits may bring misfortune on them, thus on their lineages. Although I have seen black stools, I have not been allowed to photograph them.

|

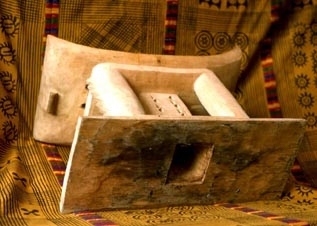

An Ancestral Stool

The actual blackened sacred ancestral stool is wrapped inside the white cloth on top of the rocks. The silver lined stool on top of the chair is revered, and a bell is attached to it as a trophy from some long ago war. It is not a black stool. The bells are common, most being originally ships bells, but moving from stool to stool depending upon the outcomes of various wars and battles.

Note that the black stool is supported by rocks, which keep it above the ground.

Language of the Dead

There is no separate language of the dead as such. To show respect to a chief in court, or an elder in her or his home court, one speaks through another. In larger and more important courts, this is formalised in the position of the linguist. It is not that a different language is used, but the linguist usually interprets to speak in more sophisticated language, more diplomatic and polite language, and more courtly language. When elders argue a case in court, they rely on a long list of oral proverbs which together form an encoding of accepted norms, morals and laws. Commoners who visit the court are more likely to know fewer of those proverbs. To them, they do not understand everything which is being said, and consider courtly language to be the language of the dead.

|

|

Daasebre Akuamoah Boateng II

In this photo, the Kwawu Omanhene was making a speech at a large Kwawu afahye. He was reading a sophisticated and detailed speech about economic development of the district. Look on the left side of the photo behind the microphone. That is the Chief Linguist of Kwawu. When the Omanhene finished his speech, we all wondered what the linguist would do, because he could not speak English. He came up to the microphone and said two words "asem pa, (good news)" and we laughed and clapped. The speech was aimed at the educated elite, and did not have to be translated specifically into Twi for the others.

Ankobeahene

The Ankobeahene (Doesn't Go Anywhere Chief) of Obo is an important elder in the Obo court. His lineage oral history states that they were here before the Akan came, spoke Guan, and were patrilineal. Seeing that the incoming Akan were powerful and organized, they felt discretion was the better part of valour, and decided to join them instead of fighting them. They converted their systems of succession, inheritance and the formation of descent groups from patriliny to matriliny.

The word "ankobea" means "does not go anywhere," and in the Akan politico military organization, they were the ones designated to stay at home while the others went to war, and to defend the home town against invaders who might otherwise raid and loot an empty town.

|

Obo Ankobeahene

Nana Ntori Denkyira II

Queen Mother

The Ohemma (female chief, mother of chief) is one of the important elders in a chief's court, being one of the "king makers" who can install and remove a chief. She does not have to be the physical or biological mother of the chief, for all elders are selected and do not succeed automatically. She is treated politically and socially as if she were the mother of the chief. When a chief's stool becomes vacant (through destooling or death) the royal lineage selects a candidate and he or she must be approved by the court. Part of the ceremony is the confirmation by the Ohemma that the candidate is "whole" (not circumcised). This is a residual from when the Akan came across the Sahara during the expansion of Islam; historically there was a large antipathy towards Islam by the Akan.

Dating from the sixth and seventh century movement of the Akan into what is now the rain forest, the Akan elders opposed Islam, and would not allow any circumcised person to become a chief. It is the duty of the Queen Mother to confirm that the chief is "whole." No matter what the physical or medical facts may be, her word is what counts.

|

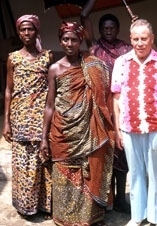

|

At her home, then later at the Asuboni afahye, Al Bartle visits the Obo Ohemma

Destooling a Chief

Everyday crimes are not seen as reasons to destool a chief. I once accompanied a chief around Accra while he sold his limousine three times. He was a bit stressed for liquidity (cash shortage) so he obtained money from three "purchasers" of the car. All purchasers were wealthy Kwawu merchants who knew who he was. There were ways to get their money back, but they would be long and cumbersome, and to my knowledge none did. Perhaps for a commoner this would be seen as theft, but not for a chief. A chief would have to do something which offended the ancestors, lowered the power or prestige of the town or lineage, or severely interfered with the ability of the chief or his court to function.

When the elders of that chief are sufficiently convinced of the need for a destooling, the Queen Mother announces that, on second thought, she may have been wrong in confirming that his body was complete. This refers to the enstoolment ceremony where the chief is lowered, naked, three times onto the selected sacred stool, and the Ohemma confirms that he is "whole."

After the Queen Mother throws doubt upon the wholeness of the chief, the Kontihene then asks the chief to give him the chief's sandals. Those sandals are very important in that the chief's feet must never touch the ground. He is black (ancestral) sacred, and doing so would short circuit the power, and remove his sacred condition. If it happens accidentally, the ancestors would be offended and sheep would need to be sacrificed to appease them. On a land inspection trip in a remote area, I, behind a chief, saw that he slipped and his foot touched the ground. I pretended it did not happen, and I kept my mouth shut, so we did not have to kill a sheep. When the Kontihene asks for the chief's sandals, that defuses the sacred power of the chief, who then becomes a commoner.

Serving Ancestors

As the youth respect and serve their elders, the elders respect and serve the ancestors (some of whom were their elders earlier when they were alive).

|

|

Young Man Pours Palm Wine for the Elder

(Who will then pour a libation to the ancestors)

Dance

The most common interpretation of the word "Asante" is "Because they Dance" or "Because of their Dance." (sa = dance; nte = because of). The Asante Empire grew and developed through warfare. The purpose of war was to open up and protect trade routes from Kumasi North to the savannah and South to the coast. Kwawu grew between two routes southeast from Kumasi to Accra, one running north of the escarpment via the Afram River (now part of the Volta lake, the other running South of the Escarpment. when the railway was built on the south side, the river route declined. The Akan did not make a practice of capturing and selling slaves. They purchased slaves from the north, mainly from Mosi speaking horse societies such as the Dagomba. The Asante trade route extended south to Elmina (named "The Mine" by the Portuguese because of the huge amounts of gold available) on the coast. When the Portuguese and Dutch heard about a people in the north called "Mosi" many assumed that this was a tribe named after "Moses," and perhaps the fabled lost tribe of Father John. The Asante, however, would not permit Europeans to travel through their territory.

The big drums do not keep the rhythm, as would be expected in a European musical group. The big drums recite poetry, using the tonal system of the Akan language. The rhythm or beat is kept by the dawuru, made of metal and hit with a wooden stick. It sounds like a cow bell, and is called, in pigeon English, Gongong.

|

|

|

An Asante war dance serves much the same purpose as a military parade in European societies, and now among the military in West Africa. It symbolizes loyalty and the political military social organization, and confirms the importance of discipline and obedience.

A war dance must always begin by moving the right foot forward in a semicircle and placing it to the right on the ground.

|

Elder Dancing a War Dance

|

Obo Kontihene Dancing a War Dance

|

Ahenkwa Dancing a War Dance

|

|

|

|

Files in the Religion set: |