Translations:

Other Pages:

CEC Training Modules

Akan Studies Site Map

Sociology for beginners

Contact

Kompan Adepa

Go to the People

Ghana Web

Housing

by Phil Bartle, PhD

Nowadays, new houses are made of cement bricks where the owner can afford to buy them. When they are made in the traditional manner, there are two basic methods: (1) sun baked clay bricks, about four times the size of cement bricks, and (2) "wattle and daub" or a frame of poles covered with earth paste rich in clay. In both cases, the outer plaster is made of high quality clay, and the job of plastering is usually assigned to women. In the North, where cattle survive because of lack of rain forest tsetse fly, the plaster is made from earth enriched not only with clay but also with the faeces of cattle. Floors and walls of homes of wealthy lineages are also painted with red ochre, a job usually done by women or slaves (thus an embarrassment to a royal who is a potential chief discovered with hands stained with red ochre, a very significant item if you learn about swearing oaths).

|

A New House

Caves

The oldest extant accommodations in Kwawu are the caves. Archaeologists dig in them because the rapid biodegradation and heavy rainfall in the rain forest make other sites barren. While there is archaeological evidence that they were used for domestic housing several centuries ago, they are now, and apparently as long as the Akan have lived in Kwawu, used as shrines of the gods, not for domestic accommodation.

|

|

Round Houses

The earliest constructed houses were apparently made of branches, and tended to be round as they were tied at the top. Elders tell me of them being used by hunters in their youth, as temporary shelters, but I was not able to see any.

The Guan made the round shelters more permanent by plastering them with clay which hardened in the sun. This process was developed into wattle and daub construction methods. As the design developed, the sides became vertical, still made of wattle and daub, but the roofs were made separately of raffia and oil palm branches. Such construction is now found only in areas north of Kwawu on the savannah, including those of the Nchumuru (an extant Guan group). Some very old houses in Kwawu that are round, are used as shrines of the older gods, those that speak Guan rather than Twi.

|

|

Round Separate Houses with Fences in Guan areas North of Kwawu

Only a few round houses remain in the rain forest today among the Akan, and are usually designated as houses of local gods.

The Guan, who preceded the Akan, built round houses, as they do still in the north in extant Guan communities. The local gods, spirits of rivers, caves and mountains, were present in the rain forest among the Guan when the Akan came. When older gods possess akomfo, they speak Guan, even when the person might not be able to speak Guan in everyday life.

Square Houses

Many of the Akan cultural traits are traced to the savannah, across the Sahara desert, from north East Africa. See Forty Days. In those (semitic speaking) areas, the square cornered house, with an open square central courtyard, was a basic pattern. Although some topologically enamoured anthropologists say that the difference between round and square houses is only in the minds of the anthropologists, the Akan people who build them see huge differences. There is a major difference in the construction of corners when building roofs. The Guan round houses were each separate structures, often in a circle or enclosed in a fenced area. The Akan house pattern was a set of joined rectangular structures with an identifiable central courtyard. This was a radical change in construction, not a figment of the anthropologist's imagination.

|

The basic Akan house pattern is square with an open central courtyard

The difference between using wattle and daub versus using large sun baked clay bricks, was mainly a difference of how permanent or temporary was the house, or how important it was. The house below is unfinished, and you can see the wattle on the right side. The wattle and daub house, below on the left, is plastered with earth mixed with fine clay.

|

|

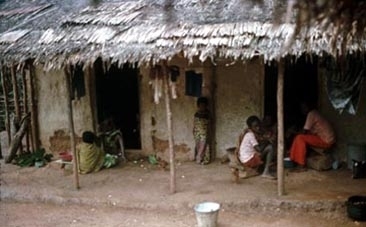

Wattle and Daub is found more in remote rural satellite villages

The wattle and daub houses are first built with poles (wattle), and then they are covered in earth mixed with fine clay (daub).

|

Making a roof from palm branches

Roofs, called "swish," were made with the branches of the raffia or Oil Palm. Later galvanised iron was used when the cocoa migration brought in money, and lately they have been using slate roofing if they can afford it. Remote villages still use the oil palm branches.

|

|

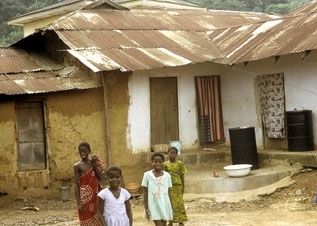

Sun Baked Clay Brick Houses Without Outside Plastering

Note how

red the earth and clay bricks are in the photo above.

|

|

Sun Baked Clay Brick Houses With Outside Plastering

In this older village house, some of the surface is breaking off so you can see the bricks behind it.

The room with the white door curtain is the room of Nansing, a powerful god.

In stool towns, where image is important, the bricks are plastered with a mixture of earth and fine clay.

|

|

Tenants usually put up door curtains –– Here there was a change of tenants

Modern Cement Houses

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colourful modern houses owned by wealthy traders and cocoa farmers

Wealthy Entrepreneurs in Obo Build Expensive Houses Which Stimulate Rumours of

Magic

|

Colourful House Used as a Bar

Wall Art

|

|

Also see bar art.

Nkawkaw

|

Nkawkaw: Commercial Town in Kwawu ─ Living above shops

Nkawkaw (literally meaning "red-red") was a minor village in the traditional oman structure of Kwawu. It was originally only a satellite village of Obomen, which is under Obo in the Nifa Division. When the railway came, between Accra and Kumasi, it took away the foot trade and the Afram river trade, and Nkawkaw grew fast like a frontier town. Then with the construction of the highway between Accra and Kumasi, Nkawkaw continued as a major commercial town serving the rest of Kwawu. The traditional (chieftaincy) structure of the Kwawu oman is slowly adapting to reflect the modern commercial importance of Nkawkaw, and the office of headman has now been promoted to chief. See: Nkawkaw Lorry Park.

See: http://www.marshall.edu/akanart//akanadansie.html