Translations:

Other Pages:

CEC Training Modules

Akan Studies Site Map

Sociology for beginners

Contact

Kompan Adepa

Go to the People

Ghana Web

Why Obo?

by Phil Bartle, PhD

Many friends and students have asked me why and how I chose Obo as the subject for doing my PhD research. The answer is a bit of a story, so I have decided here to relate that tale.

It starts in 1965. I was finishing up my BA in economics and sociology at UBC. May was a watershed month for my life, as I had a new commission in the RCAF, and was invited to do a military career in logistics in the Canadian air force. I had been a member of the university International House because of my interest in international development. I had applied to Cuso, and was accepted to go to Kenya to teach economics. I chose the international career, I think, because I could then grow my beard.

I spent the summer in a tent on my parents’ fruit orchard, under the cherry trees, learning Swahili out of a book, no live informants, no tapes, not even geography books. A Kenyan friend, with whom I had shared a lab table in our first year course in chemistry, who had encouraged me to go to Kenya, had taught me one song on my guitar. My preparation.

|

On my father's Okanagan cherry orchard

I took the train east at the end of summer for our Cuso orientation, starting at York University. The first thing I learned was that my contract in Kenya had been cancelled because Oginga Odinga, who was vice president then, had pushed through a law that said no foreigners could teach interpretative subjects. Would I like to stay for the orientation while they sent telexes to all the Cuso offices to see if there was another post somewhere? Having said my goodbyes and not wanting to go home, and still eager to go anywhere, I said yes. So I stayed for the six week orientation. It continued on for a few more weeks for the Africa volunteers only at McGill.

Prof. Peter Gutkind was one of the presenters, telling us to eat insects and participate fully in the local cultures. (A few years later I was to become his research assistant when he visited Ghana and I was lecturing at the University of Cape Coast –– I told him I had eaten grubs found in rotting oil palm tree roots and they were delicious).

|

Grubs

The two dozen Cuso volunteers going to Ghana had daily lessons in Twi, even those who were going to non Akan speaking locations. I got no language lessons because we had no idea what would be my host country, though we suspected it would be somewhere in Africa. I could not ship my trunk because we did not know where it should go.

Finally, three days before we were to leave, I found out that a Catholic seminary and secondary school, then called St Peter’s College, wanted me to come and set up their economics programme for them. Sure. It was in a little village called Nkwatia, in the South Kwahu District, Eastern Region of Ghana.

I contacted the two Ghanaian international students hired to teach Twi to the volunteers, and asked them to at least teach me "Please," "Thank you," "Hello" and "Goodbye." They told me that instead of "Hello," you said "Good morning," "Good afternoon," or "Good Evening," depending on the time of day. The reply would be "Yaa nua." They were not quite accurate in teaching me the reply.

|

Arrival at the airport

We flew, all sitting backwards, in an old RCAF Yukon transport plane, stopping to sleep in Marville, France and annoying our hosts by singing "We want to go to Andorra" and other peace songs in the officers’ mess. Barney (Walter) Dobson on banjo, myself on guitar. Not appreciated on a Canadian military base. I did not mention that I had resigned an RCAF commission a few months earlier. I was the only one with my trunk with me on the plane. The plane stopped in several countries on its way all around the world, so I got my first glimpse of men holding hands, a police officer and civilian, on the tarmac in Abidjan.

Finally in Accra, we did two more weeks of orientation, with Ghanaian presenters, very interesting, at the University of Ghana. Then, on the last day, in the evening, after all the others had been picked up, a little Volkswagen came for me and my Canadian colleague and we drove all night in the rain to Nkwatia. At one point the car stopped in the dark; the gas mechanism from the foot lever had broken, and the young driver was stumped. I fixed it with a piece of cord on my suitcase. I wanted the interviewer at my Cuso interview to know, because he had asked me about being able to fix a car miles from anywhere when it broke down in the rain.

Nkwatia was on the top of the Kwawu escarpment, where the temperature was a few degrees cooler, and where there were a few more centimetres of rain. Climbing the escarpment was scary.

|

The south side of the Kwawu Escarpment

A few days later, I was sitting on the stoop of our bungalow with a newly met Ghanaian friend and colleague. It was about five forty five and just starting to get dark as it does exactly at six every night so close to the equator. The school was on the edge of the village, and one of the paths to the farms went right past all our bungalows. A woman with a huge load of firewood on her head, an axe and a hoe, a child in tow, and apparently one on the way, passed us on her way back to Nkwatia after a very tiring day on her farm. Greetings are very important in the culture, so she called out to us, including a greeting to me, "Kwasi Obruni" (European born on Sunday), good evening." Here was my first chance to practice my little knowledge of Twi, so I replied "Yaa, nua."

Her response had a little bit of annoyance in it, so I asked my Ghanaian colleague what she said. He said you replied with the reply for brother which is used only for known friends and younger brothers and sisters. The students in Canada thought that I, a Canadian teacher, would be talking only to colleagues and students. She was a mother and older than me, so I should have answered "Yaa, enna." Well, I was embarrassed; I learned the Twi for what she said, and vowed to learn the language as completely as I could while I was there. The first thing I learned was that greeting replies depended on status of the greeter. Later, I discovered when going much deeper into the culture for my PhD, that the greeter’s status could also include her or his ntorכ, a spiritual category inherited only from one’s father.

I set up the economics programme, but had only lower sixth form to teach in the first year, so they gave me a maths course in O level just to keep me busy. I still had time to go out to the villages every weekend, and to travel around, mostly locally, to explore and discover what I could, and to learn the language and customs. I bought a Honda 120 motorcycle in Kumasi, and used it to get to more remote locations. My salary was N¢120 per month (about $150 Canadian) and I could easily live off half of it.

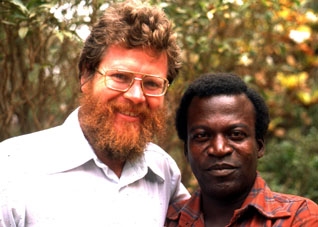

I became close friends with several of my fellow teachers, and enjoyed travelling and moving with them. My best friend, however, was Peter Kwaku Boateng, a blacksmith and plumber. He had learned to smith as an apprentice, and how to do plumbing from a Catholic brother, and we met when he came to set up the water system in my bungalow. Peter and I travelled by local transport all the way into Côte d'Ivoire together, and to Abidjan, learning that his pigeon French and my sad high School French did us quite well, between us (although we could not understand each other in French), but also that Twi was spoken in the east and south of Ivory Coast and so we used it most. Coincidentally, Peter was of the Asona clan, and was from Kwawu Tafo (where the royals are Asona –– where Sjaak van der Geest did his Kwahu research), so later, when I became a member of the Obo Asona clan, he became my brother.

|

With Peter Kwawu Boateng, Blacksmith, Plumber

Another good friend I must mention is Peter Kwame Appah Kissi, a student at St. Peters my first year, and fellow teacher and bungalow buddy the second. His father was a wealthy Obo merchant, and was later to provide me accommodation when I was in Obo to do my PhD research.

|

My Honda 250 on long distance trek

One day I was coming up the steep and winding one-way road from the lowlands, near Nkawkaw, up the Kwawu escarpment, and I found an old Mercedes Benz limousine stopped on the side of the road. A young man was pacing around, very agitated, and an old man was sitting inside. The young man told me he wanted to go to Nkawkaw to get a "fitter" (mechanic) to repair the car, but could not leave the old man alone. I supposed the old man was ill or fragile, not knowing yet that he was a man never allowed to be alone.

I said that, if the old man was brave, he could ride on the back of my motor cycle, that I would take him home, and the young man could go to Nkawkaw to get the fitter. They took up the challenge. The old man was not a coward by any stretch of the imagination. When he got onto the bike, he dropped a huge chain with keys and the young man, slightly agitated, picked them and the old man put them in his pocket for the ride. I learned later that he would always be with those keys.

|

When we got to the top of the escarpment, by a town called Obomeng, he indicated that he wanted us to turn left on the "T" junction. I had not yet gone in that direction before, because a right turn would lead us to Nkwatia and most of the towns in Kwawu. A few kilometres to the west we rounded a curve and I saw the most incredible town I had yet seen in Ghana, three, four and five storied buildings, a clean and neat atmosphere, the smell of money. The old man asked me how I liked "his" town. I, not knowing the implication of him using the word "his," told him it was very beautiful.

|

"Sikafoambantem" (The rich folk came late) a wealthy neighbourhood of Obo.

Past all the new storied houses, up a broad main street, we entered an older part of the town, and to his "house." It had huge wide open doors, several large drums and other things sitting around, and I began to realise this was not an ordinary man. A young lad, later I knew to be the son of the Gyaasehene, was there, and he was able to act as interpreter because my Twi was still only rudimentary. This was the Chief of Obo, and the Obo Chief was the head of the Nifa (Right Wing) Division of Kwawu, a very powerful man indeed. Nana Kofi Bediako. He offered me a beer, which I happily took, and we each drank a beer and made polite conversation, he in stumbling English and I in stumbling Twi. He encouraged me to spend my weekends, when not teaching, visiting him in Obo, and especially to come during an Akwasidae, every sixth Sunday. This was further stimulation and opportunity for me to learn more Twi.

So I spent weekends with him, and sometimes with his Kontihene, who was usually in Accra selling hardware. The Kontihene was the best source of customs, stories and culture, more erudite than the chief, and who had better English, and the chief was happy to have me ask more and more questions of the Kontihene, Nana Noah Adofo Aduamoa II.

I had talked about adoption even before I understood what matriliny was, and how the abusua (matrilineage) was the basis of social and political organisation). One day the old man said bring a bottle of schnapps on the next Akwasidae, and the Chief Linguist poured part of it to the gods and ancestors, saying that I was now Oboheneba Nana Kofi Bediako - Akenten, son of the Chief of Obo. I was happy to take his name, and they knew Europeans took their father’s names. That was fairly rare in Kwawu society, although the man who later adopted me as his matrilineal nephew, Nana Kwame Ampadu, was the father of the bandleader and singer, Kwame Ampadu, the same name, whom he had taught so many traditional customs and stories that the son used in his famous African Brothers dance music.

At the end of two years as a volunteer, I was dissatisfied with the course I had to teach, with its Keynesian economics, for it was based on the Samuelson textbook. It applied neither to (1) the national economy, based on Nkrumah’s socialism followed by military dictatorship, both of which had price controls and so called "essential commodities," nor to (2) the local markets, run mainly by women, which had their roots in centuries of customs and alliances. I also wanted to see how poverty was felt around the world, so I took a year to get home, travelling fifth class by way of East Africa to South and then Southeast Asia, and I went into Economic Anthropology at my Alma Mater, UBC, because of Cyril Belshaw and Harry Hawthorn, and its reputation for top class economic anthropology.

When I finished my MA, I worked for a year as the BC co-ordinator for Cuso, then set up the Anthropology Department at Capilano College. Although I was admitted to the PhD programme at UBC, I also won a Commonwealth scholarship paid for by the Government of Ghana. My supervisor, Prof. Harry Hawthorn, advised me to go for the African experience, as I already had a BA and MA at UBC. My MA thesis was about migration and decision making, and based on some African data I had, so I decided that I wanted to look at an extended or dispersed community, as migrants travelled yet maintained their links with their home town. I vaguely thought I could do an ethnography of the dispersed community.

When I got to the University of Ghana, Legon, I immediately made a trip to Obo. I had heard that my old friend, the chief, had died. I asked Peter Kwame Appah and Peter Boateng to accompany me, and they explained that this was the one instance where you took an open bottle of schnapps into the chief’s court, a grieving son was so distraught that he broke custom (only an unopened new bottle of schnapps was normally brought to the chief) and drank some of the alcohol to assuage the grief. The irony was that I really was sad to learn the old man had "gone to farm," as was the polite way of stating he had died, and I had missed the funeral.

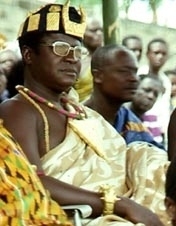

Several of the elders remembered me, notably the Chief Linguist, the Kontihene and the Gyaasehene. The Chief Linguist remarked that I had learned custom and had brought an open bottle of schnapps (but also a closed one just in case). The new chief, Nana Asiamah II, formerly a police sergeant, welcomed me, and heard my story, well embellished by the elders I just mentioned. He has a great sense of humour and explained to me that a chief was succeeded by his matrilineal nephew, not by a son, and inherited all the liabilities and assets of the old chief. He would not say if I was an asset or liability, but confirmed that I was his son, and he was happy to see me. A father’s duty usually included paying school fees, he said, but since the state (Ghana) had paid mine, he would help me in a different way. If I promised to keep their secrets, he would instruct all the elders and sub chiefs, and all the traditional priests and priestesses, to open their doors and their histories to me, so I could make my ethnography of Obo. I had made a rough explanation of what my PhD study would be, but he insisted that the best place to do it would be Obo. I promised and he was true to his word. I got access to many ceremonies, rituals, histories, secrets, genealogies and customs that few commoners in Ghana knew about, let alone witnessed. (See Black Linguist Staff). It was worth, in ethnographic value, far more than the scholarship itself. I have kept the secrets to myself, for that does not hinder my sociological analysis or reporting to do so.

|

Nana Asiamah II, Obohene, Nifahene of Kwawu

I went back to Legon, and wrote up my proposal. Although the general feeling in the Sociology Department, especially by the Head, Mr. De Graff Johnson, that the study of chiefs and their cronies was archaic, and that I should be doing "modern" sociology (surveys and whatnot), my supervisor, Dr. Dzigbodi K. Fiawoo, who had done a study of Ewe magico religious rituals and beliefs (although he was more interested in their decline) in Scotland, supported me. After a century and half of European Christian proselytising, many educated Ghanaians tried to look "modern," and were ashamed of their historical culture, especially those practices that involved gods and ancestors (that the European missionaries called "devil worship"). My proposal was finally accepted, so long as I added a household survey and promised to look at the effects of urbanisation on family social organisation.

Later, at the invitation of Nana Kwame Ampadu, father of the African Brothers leader, Kwame Ampadu, Gyaasewahene of Obo, Head of all the Obo Asona lineages, and relative of the Okyenhene (Paramount Chief of Akyem Abuakwa) we performed a similar adoption to bring me into his matrilineage, the Asona or White Raven. He designated an old woman in the lineage as my "mother." We went together to Kyibi at the death of the Okyenhene, I in my official capacity as a member of the mourning lineage. When Nana Ampadu went to farm, the lineage elders asked if I wanted to succeed him. I asked forgiveness, but I had responsibilities back in Canada, was honoured by the suggestion, but respectfully declined. They told me I was still always welcome in the lineage home and could enter the ancestral stool room whenever I wished.

|

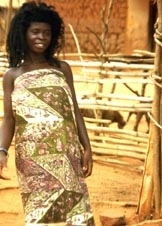

Seeing that I was a young active man, the elders were concerned that I might be a bit promiscuous. A newly confirmed priestess, a woman of one of the Obo Amoakade lineages, from a remote village on the northern slopes of the escarpment, came to confirm that she was possessed by the God, Nansin, a river inside a cave, and a powerful historical god of the region. A priest or priestess can never marry a human, because she or he is the "wife" of the god or goddess. She could take on recognised lovers (mpna), however, so they suggested that she and I be hooked up that way; I could learn more about traditional religion, and avoid being too promiscuous. She was amused, and delighted, and opened many more doors for my learning, especially about the herbs she collected from the rain forest. The main gods in Obo itself, and their priests and priestesses, also welcomed me, for I was respectful, unlike the Christians who abused and insulted their gods.

|

Nana Adwoa, Nansing Komfo, Aboam

Other priests and priestesses taught me, too. The Tano God was the stool god of Obo, brought from the headwaters of the Tano River in what is now Brong Ahafo, with the Amoakade. Asuboni (bad or naughty water ─ a nearby river that ran from Obo across the escarpment to empty into the Afram on the north side of the escarpment) priestess was one of my main informants on the history and practices of the local gods (who had also been the gods of the Guan, previous patrilineal inhabitants of Kwawu before it was converted to matrilineal Akan.

My Twi improved. (I developed and used an Aural method). By the end of the two years as a volunteer, I spoke better Twi than any of those who had received six weeks language training in Canada. When I returned, I learned the proverbs, and the "language of the dead" (wherein elders in court can communicate ideas that commoners could not understand). I learned that my thought patterns were different when thinking in Twi than for English.

There are mild rivalries between the chiefs, and one upmanship was a great game between them. The Obo chief was one up on all the other Kwawu chiefs by having me. Historically, Obo led the faction in favour of Asante and against the Swiss missionaries when Kwawu declared independence from the Ashanti Empire (1883). The Paramount and Adonten divisions were in favour of joining the missionaries. The Benkum Division of Kwawu had its alliances with Akyem Abuakwa. Remnants of those historical alliances are found in residual games between the chiefs today. Of course the Obo Chief drew me into those games. I was his asset, and I learned more as a result.

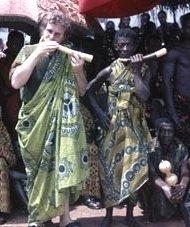

I learned the Obo and Kwawu tattoos on the horn, and blew officially for the chief on public occasions. I followed the chief into the big church at Abetifi during a big public service, and the doorman, while keeping out all the drummers and horn blowers from coming inside the church (devil’s music) was too surprised to see me, a young Obruni, that he let me inside, and the Obo chief then signalled for me to blow his tattoo on the horn in the church. The heavies in the church were not amused. Fun.

|

Learning to blow the Obo Horn

At a big public durbar (afahye) in Abetifi, the Paramount Chief of Kwawu (who also had a law practice in Tema), saw me behind the Obo Chief with the horn. He asked me over to his side of the field. He then asked me to play the Obo tattoo. When I did he sent his congratulations over to the Obo Chief. Then he challenged to Obo chief that his boy could also play the Kwawu tattoo. The Obo tattoo and the Kwawu tattoo are very similar. When the Obo leaders taught me the Obo tattoo, they also taught me the Kwawu tattoo, and told me never to play it, or the Obo Chief would have to sacrifice a sheep. When the Paramount Chief asked me to play the Kwawu tattoo, I looked across the field and got reassurance from the Obo Chief and elders. I played what had earlier been forbidden to me, the Kwawu tattoo. The paramount chief laughed with delight, and sent a sheep across the field to the Obo chief. (I play saxophone, but it is a reed instrument, whereas the chief's horn, from a buffalo, is played in a manner similar to a trumpet, with the lips vibrating). The educated Ghanaians in the crowd did not know exactly what it was all about, but were amazed that I could be so courageous (chutzpah?) as to play among the chiefs.

|

Daasebre Akuamoah Boateng II, Omanhene (Paramount chief) of Kwawu

I learned how to act as a linguist, and pour libations (prayers) to the gods and ancestors. The Obo chief took delight in asking me to pour libations when Christians came to the court, with their bottles of schnapps (many being teetotallers) to get permission to open a church, clinic or school. Obo was still seen (in a mild, non confrontational way) as the main opposition to Christianity in Kwawu, and the Obo chief delighted in irritating the missionaries by calling them his "brothers and sisters in Christ," they full well knowing that he was traditionally possessed by his own matrilineal ancestors. In fact, all churches were welcomed in Obo, and tolerance was a way of life.

Talk about participant observation! I was comfortably strapped in with workable seat belts, and ready to fly.

Obo had chosen me.

Files in the Social Organization set: |